After some months of dicking about in Europe, reading about magnanimous Europeans from books in their grand collections, I may hold a rose-tinted view of the place. Certainly, I am under no illusion that international cooperation was much up to snuff in the Middle Ages, the high point perhaps having been reached in 1204, when the Venetians, the Genoese and the French managed to overcome their ancestral hatred for one another just long enough to sack Constantinople.

I wouldn’t wish any of this to be construed as disloyal to the people’s will, so rather than dwell on the long history of cooperation that has existed between England and Burgundy, Normandy, the Holy Roman Empire, Scotland, Denmark, Navarre, Anjou, any number of territories in Germany or our oldest ally Portugal, I have been thinking in very literal terms about Europe. Secundum John Trevisa:

Europa is þe þridde deel of þis worlde wyde, and bigynneþ fro þe ryver Tanais and þe water Meotides, and strecceþ dounward by þe norþ occean anon to þe endes of Spayne at þe ylond Gades, and is byclipped by þe est and also by þe souþ wiþ þe grete see. In Europa beeþ many prouinces and ylondes, þe whiche now schal be descryved.

What a lot we have learned! This information ultimately comes from the seventh-century Visigothic polymath Isidore of Seville, perhaps on par with openly gay Olympic fencers for general rum-ness, so we may have to look nearer afield. The reassuringly English Bartholomew Anglicus quotes Paulus Orosius, also rather foreign for this political climate, having been born in what is now Galicia:

Europae regiones et gentes incipiunt a montibus Ripheis Meteodisque paludibus que sunt ad orientem descendentes ad occasum per littus septentrionalis occeani. [The regions and races of Europe begin from the Riphaean mountains and the Maeotic swamps, which are in the east, extending in the west to the shore of the northern ocean.]

A great deal more helpful, I’m sure you’ll agree.

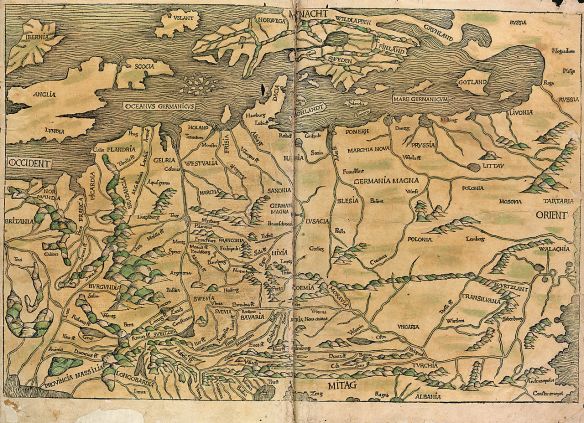

When medieval western writers – specifically, Latin writers – discuss Europe, it is often in relation to Africa and Asia, and always begins from the idea of its physical dimensions. Its borders are the River Don, the Mediterranean and the Encircling Ocean; its larger territories have the same names in 500 as they do in 1500; lakes, mountains and rivers may be more or less prominent, depending on the origins of the writer, but none are so prominent as those mentioned by Pliny the Elder. The physical geography recorded in these accounts makes no reference to rulers, treaties or wars. It isn’t dishonest on the part of the writers; this sort of information doesn’t generally belong in that sort of book.

Spot the unelected bureaucrat!

Bartholomew does not go so far as to write any of Aquitaine’s history when he describes its rivers and its fertile soil, but he does give some space to the vague idea of national character. The Venetians love justice, the Swabians pick fights, and the Scots are ferocious to their enemies. Bartholomew being an Englishman, the English are singled out for praise, but the descriptions of the natural bounty of the territory Anglia come from Pliny and Bede. While a quasi-nationalist sentiment guides his pen, Bartholomew’s facts are already over a thousand years old.

A thousand years ago, England was part of a wider Scandinavian empire. Seven hundred years ago, it had been decisively repelled by its quondam et futurus neighbour Scotland. Three hundred, it had unified with Scotland and was ruled by an Elector of the Holy Roman Empire. One hundred, it was at war in Europe, and would shortly be again. What happens next to England in particular, and the British Isles in general, is of course up in the air. It could become a post-apocalyptic wasteland of student Macbeth proportions; there could be a new golden age of honey-flowing trees and piping dryads; neither is entirely likely.

But I cannot help but think of Portugal, with whom we have been in alliance since Chaucer was alive. As our old friend Cicero writes in De amicitia,

If you should take the bond of goodwill out of the universe, no house or city could stand. […] For what house is so strong, or what state so enduring that it cannot be utterly overthrown by animosities and division?

Bartholomew, writing in the 1240s, did not make any special allowance for Lusitania and the character of its people. He wrote nothing to allow us to conjecture how its people would respond to an animosity emanating from England for as long as I can remember, and above all in the past year. Perhaps the Lusitanians, like the Venetians, love fairness and won’t stomach our animosity. Perhaps, like the Scots, they are ferocious to their enemies, and our government has very much treated them as if they were just that. If the upshot of this half-baked whim, of our losing a friend of forty years, is that we lose a friend of six hundred and forty, I for one shall be rather cross.