With a new term and new students, I find myself answering a great deal of questions about What Life Was Like in the Middle Ages. Because the students appear to be sober, thoughtful types, these are usually questions on the practice of religion, the legal status of women, and popular views of history. Aside from the occasional treat – ‘How much of Game of Thrones is real?’, not in itself a bad question – the tone of our classes is rather serious, and thus my leisure time has to be given over to burning cultural inquiries like ‘Were medieval people drunk all the time?’

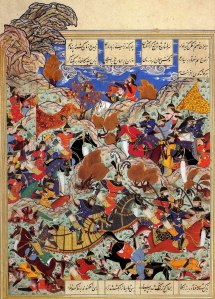

It’s a matter of great historical import, probably. As any fule kno, alcohol kills bacteria and is therefore safer to drink than pond water, whatever current NHS guidelines might say. Calorie-rich and alcohol-low small beer would have been both nourishing and tolerably hygienic. But would it really get people drunk? In the past, I’ve written about feasts and the blow-out on expensive, imported wines that these entailed. These may have caused some stinking hangovers but are by no means common. Yet medieval depictions of drunkenness abound, from manuscript images of vomiting and bar-brawls, to the chaos of Holofernes’ banquet in the Old English Judith:

Ða wearð Holofernus,

goldwine gumena, on gytesalum,

hloh ond hlydde, hlynede ond dynede,

þæt mihten fira bearn feorran gehyran

hu se stiðmoda styrmde ond gylede,

modig ond medugal, manode geneahhe

bencsittende þæt hi gebærdon wel.

Swa se inwidda ofer ealne dæg

dryhtguman sine drencte mid wine,

swiðmod sinces brytta, oðþæt hie on swiman lagon,

oferdrencte his duguðe ealle, swylce hie wæron deaðe geslegene,

agotene goda gehwylces.

[‘Then Holofernes, the gold-giving friend of his men, became joyous from the drinking. He laughed and grew vociferous, roared and clamoured, so that the children of men could hear from far away how the fierce one stormed and yelled; arrogant and excited by mead, he frequently admonished the guests that they enjoy themselves well. So, for the entire day, the wicked one, the stern dispenser of treasures, drenched his retainers with wine until they lay unconscious; the whole of his troop were as drunk as if they had been struck down in death, drained of every ability.’ Ed. and trans. by Elaine Treharne]

As you may know, Holofernes suffers no hangover because he wakes up dead.

Moral disapproval of drunkenness in the period flows at least in part from its association with the deadly sin of Gula, gluttony. William Langland does not record whether the ensuing bacon sandwich is to be counted as the same sin as the earlier pints, so my investigations have taken on a new urgency since I discovered in The Forme of Cury what can only be described as hangover food of the highest order. Owing to a Europe-wide shortage of potatoes in the Middle Ages, I can but assume that such delights as Malaches of pork filled the social and dietary function of a carton of cheesy chips. So, just in case my students begin to ask more flippant questions, I cooked it.

Malaches of pork (The Forme of Cury).

Hewe pork al to pecys and medle it with ayren and chese igrated. Do þerto powdour fort, safroun and pynes with salt. Make a crust in a trap; bake it wel þerinne, and serue it forth.

I bought minced pork, because I’m lazy, but made my own shortcrust pastry, with which I untidily lined a shallow round tin. With 500g of pork, I mixed in 4 medium eggs (beaten) and about 50g of grated cheddar, which in retrospect was not enough. My powdour fort recipe was somewhat vague, and consisted of:

- ½ tsp ground ginger

- ½ tsp ground mace

- ½ tsp ground black pepper

- ½ tsp ground nutmeg

I mixed it into the pork-egg-cheese along with about 50g of pine nuts. Saffron is expensive and it was nobody’s birthday. I then spread the pork mix evenly into the pastry-lined tin, and put it in a 190°C oven for 45 minutes. It was served forth with the old favourite spynoches yfryed (as before).

Reader, it was delicious. My friend Jen, who took the photograph, heartily agreed, and neither of us was even hungover. It had the attitude of a Chicago deep pan pizza, if Chicago were in the North East of England. I wonder whether more cheese may have given it an oozy, stringing consistency whilst hot, but the leftovers were pleasant enough cold. The spice was warming, not overwhelming, the pine nuts exceeded themselves; even the saffron (which, you will recall, I did not use) was apt. We had it with a Provençal rosé of which Richard II might have approved. My blood vessels have yet to recover.

All of which rather side-tracked me. For how can I answer a serious cultural question about medieval drunkenness with an anecdote about a time I made a really nice tart? How can I teach the literature of Ricardian England when I’m thinking about the unexpected pleasure of a hypothetical royal hangover? Who is Epicurus owene sone, and how can I meet him?

Next week: The peasants threaten to revolt when the bakery moves across the channel.