A brief update from the damps of February. This week I considered writing something about romance (not Romance), or Forty Seven Medieval Ways to Neck a Bottle of Wine, but today is a special anniversary for two very special people. That’s right: on this day in respectively 1294 and 1405, Kublai Khan and Timur the Lame both died. Two out of three favourite medieval warlords rate today as the best day to die!

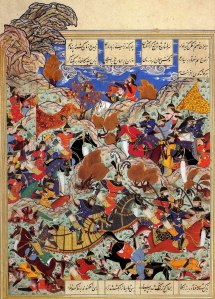

It is a bit weak to talk of the ‘achievements’ of men who ruled over substantial parts of Asia, oversaw vast construction projects and whose empires could scarcely survive them. In part it is a question of scale and ambition. Both men seem to have modelled themselves on Genghis, with all the ruthlessness and brutality that entailed. In another part, they simply feel unreal as historical figures.

Bro, do you even pillage?

What I know of these men I know primarily from European sources. Specifically, from the Livre des Merveilles du Monde of Marco Polo and Kit Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great. In many ways, this is like exploring medieval history using only the Arts and Crafts movement and Game of Thrones – or, precisely how most people explore medieval history.

The mythic quality of the historical figures easily spills into depictions of them. Rustichello’s Kublai is a King of Kings, with vast wealth, vast lands and a vast court, a latter-day Cyrus whose historical truth is more than a little tainted by legends of Prester John. Marlowe’s far later creation is an orgulous tyrant, crushing rivals and burning cities in scene after scene. Handel’s Tamerlano is pretty dreadful, with its three hours of da capo arias. Netflix’s Marco Polo is almost worse. Somehow, every one of them has a ring of truth.

The moral: enjoy your warlords in moderation.