A brief update from the wintery wastes of pre-post-Brexit Britain, and tomorrow is a very big birthday for medievalists, historically illiterate anti-Europe wonks and fans of Paul Kingsnorth alike.

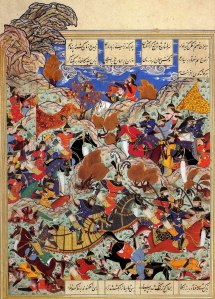

That’s right! October the 14th is the 950th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings.

William, you smug prick.

This cataclysmic event marked the end of five hundred years of Germanic dominance in England, and the beginning of 950 (and counting) years of a legal code, social hierarchy and system of land ownership enshrined by the French descendants of a Scandinavian mercenary. That for the first five centuries of which were run in close accord with the edicts of priests of a Levantine religion, living in central Italy, only one of whom was ever English. And that for the past four hundred years have been exported to places un-thought of by any Norman administrator – places whose existing populations did not want us, and whose languages and civilisations were many thousands of years older than ours. But certainly now we’ve had enough of ‘meddling’, and egged on by an American-born narcissist of mixed Turkish-Russian-French ancestry, and the graceless descendant of French Huguenot refugees, we’ve jolly well told those ghastly Europeans so.

One historical irony emerges from this mess.

I’ve been teaching about language and dialectal distribution in medieval Great Britain, and the maps that I have badly drawn for this purpose are covered in arrows: pushing west from Kent and East Anglia, zigzagging across the Scottish border, plunging inland from the Northumbrian coast, like armies have done since the Romans left. The medieval chroniclers liked to claim that the British (who were Trojan) were conquered by the Saxons (who worshipped horses, or something) because of their sinfulness. The Saxons then squandered Providence’s favour, and the Normans were able to conquer them.

Despite their monumental uninterest, my students knew that the linguistic remnants of the pre-Roman British are to be found in Wales and Cornwall, both of which areas voted Leave. Now the pound (sterling, steorling, OE) is tanking as those nefarious experts suggested, the Scots are calling for independence and Marmite, invented by a German and marketed by the Dutch, is at the centre of a hostage situation. I can imagine that Wales and Cornwall are watching what is threatening to become a götterdämmerung for the English, and as the destruction spreads they approach the Anglo-Saxon and say softly, ‘Cymbeline sends his regards.’